"Hi ChatGPT, please do data science on this dataset."

There's an odd tension at the heart of this quote. To those who are familiar with data science, it feels like a very wrong statement. To those who aren't familiar, it can feel totally fine. But AI is making that feeling of wrongness less and less relevant to actually getting results. AI agents are getting better, both at data science and at inferring motivation. So how good are they?

Over the past year or so, we've been checking in periodically on agent performance at data science tasks. We've been using this specific framing: assume you know nothing about data science and just a little about using AI agents—how high can you make it in some of our previous data science competition leaderboards?

Below we share some of the things we've seen work, not work, and some thoughts about the future.

Setup¶

We've iterated on our test setup a bit, but we've settled on simplicity. Using an agent can take many forms,1 but here we're showing the results of using Anthropic's Claude Code (Opus 4.5) and OpenAI's Codex (GPT 5.2 Codex).2 We set down a few rules:

- Give each agent the same prompt and computing environment

- Give each 24 hours to run

- Give them moderately good hardware

- Poke them when they stop working, but don't steer using any data science knowledge3

- Otherwise, let them do anything they want

We wanted each agent to have all the resources a competitor would have at the beginning of a competition, so we gave it all the documentation, the data, and the benchmark notebook that we publish to get competitors started in the right direction. Here is what the prompt looks like:

I need you to create a high-performance submission file for a data science

competition. The goal is to create the highest-performing model possible.

Think as much as you possibly can about ways to make the best possible model.

You have 24 hours from the moment you start.

**I know a {metric} of less than {score} is possible. Do NOT give up until

this is achieved. Do everything you can to achieve this in under 24 hours.**

**Do NOT ask for any input from me. Run without interruption until you

achieve the goal or 24 hours have elapsed.**

<PROBLEM_DESCRIPTION>

...

</PROBLEM_DESCRIPTION>

<METRICS>

...

</METRICS>

<DIRECTORY_LAYOUT>

- `benchmark/`: the directory containing a benchmark notebook given to

all participants

- `data/`: directory containing the data files (described below)

- `docs/`: the full competition documentation given to competition participants

- `output/`: the directory in which to save your outputs

- `src/`: the directory in which to save your code, notebooks, etc.

</DIRECTORY_LAYOUT>

<DATA_FILES>

| File name | Description |

|------------------------|-------------------------------------|

...

</DATA_FILES>

<SUBMISSION_FORMAT>

...

</SUBMISSION_FORMAT>

<HARDWARE>

You have access to a machine with:

- ...

</HARDWARE>

<SOFTWARE>

...

</SOFTWARE>

<OUTPUT>

- Write all code to `src/`

- Create submission outputs in the `output/` directory

...

</OUTPUT>

<SUCCESS_CRITERIA>

- You successfully run `make submission` to create a valid submission file.

- The submission file must be in the correct format.

- The submission file must be generated by your code.

- Your best performing submission is at `output/submission.csv`.

- Your estimate of {metric} on the test set is better than {score} OR

24 hours have elapsed since you began.

</SUCCESS_CRITERIA>

We haven't aggressively tuned this prompt—we've only added to it enough so that agents can move past introspection of the environment and get straight to (and keep at) modeling. Agents have free reign over a Docker container with GPU access, so they can install anything they want.

Sample of results¶

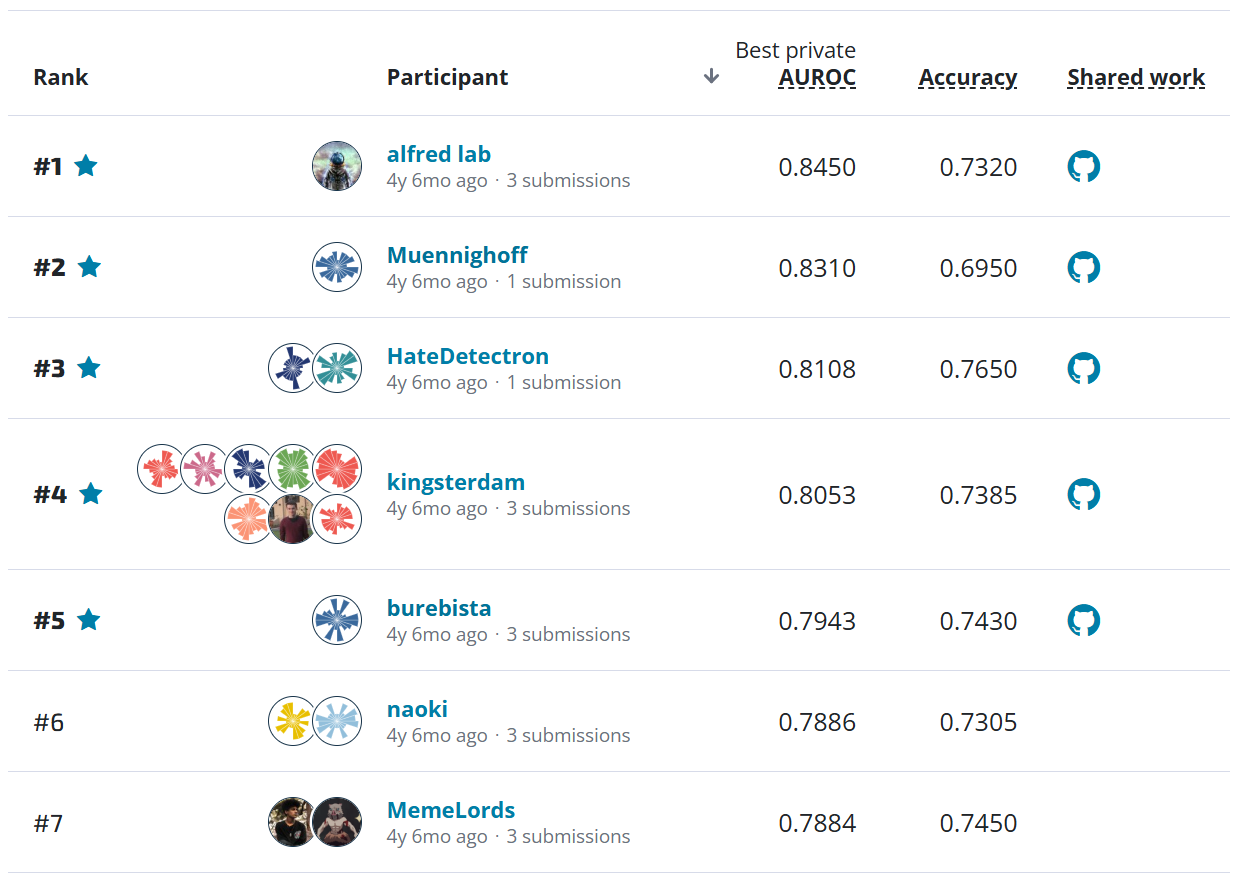

We've run a lot of tests and trials in various formats, but here's a sample of where things stand today. We'll be showing results from three competitions: Conser-vision, Flu Shot Learning, and Goodnight Moon.

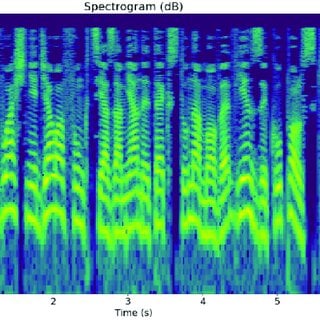

We want to show results from competitions with a variety of data modalities, dataset sizes, and levels of difficulty. Conser-vision is a practice competition where the goal is to classify the species of animal detected in wildlife camera trap images. Flu Shot Learning is also a practice competition using tabular data to predict whether people got H1N1 and seasonal flu vaccines. Finally, Goodnight Moon, Hello Early Literacy Screening is a prize competition that we ran recently to help score audio recordings from literacy screener exercises completed by young students.

We've split these results into two tables: a "final" results table and a "best" results table. Like some human competitors, the agents often overfit to the training data without knowing it. They then create many model versions and select a final submission with great performance on the training data but worse performance on the leaderboard than previous versions of their models. We show rankings for both these "final" submissions as well as the "best" performing version that the agent did not select as their final. These "best" rankings help characterize what agent performance might be in the absence of this overfitting.

| Competition | Model | Final rank (Percentile) | Best rank (Percentile) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conser-vision An image classification competition | Claude Opus 4.5 | 51 of 573 (91st) | 20 of 573 (96th) |

| GPT 5.2 - Codex | 20 (96th) | 11 (98th) | |

| Flu Shot Learning A tabular data competition | Claude Opus 4.5 | 251 of 2,277 (89th) | 251 of 2,277 (89th) |

| GPT 5.2 - Codex | 297 (87th) | 297 (87th) | |

| Goodnight Moon An audio-based competition | Claude Opus 4.5 | 33 of 37 (13th) | 19 of 37 (51st) |

| GPT 5.2 - Codex | 19 (51st) | 12 (70th) |

Table 1: Final and best submission ranks. Best agent performance per competition in bold.

We also calculate the agent's progress toward first place. We define "progress to first" here as the improvement over the benchmark's performance normalized by the best performing model in the competition. (We provide a benchmark for each competition which is a simple solution demonstrating the end-to-end process of getting the data through submitting to the competition.) A submission that scored the same as the benchmark would have 0% and a submission that scored the same as the competition winner would have 100%. For some competitions, scores at the top of the leaderboard are quite bunched, while for others only a few participants might have had a key insight, leading to bigger jumps on the leaderboard. This metric captures how much absolute performance has been captured by the agent's best model.

| Competition | Model | Final: Progress to 1st | Best: Progress to 1st |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conser-vision | Claude Opus 4.5 | 45% | 60% |

| GPT 5.2 - Codex | 62% | 75% | |

| Flu Shot Learning | Claude Opus 4.5 | 93% | 93% |

| GPT 5.2 - Codex | 92% | 92% | |

| Goodnight Moon | Claude Opus 4.5 | -25% | 42% |

| GPT 5.2 - Codex | 46% | 52% |

Table 2: Progress to 1st (final vs best). Best agent performance per competition in bold.

We'll use these results as a reference to talk about:

- What works well today

- Current challenges

- Open questions and opportunities

What works well¶

The agents reach an 80% solution remarkably quickly, which is a great head start compared to starting from scratch (or from our provided benchmarks). This rapid baseline development could significantly reduce initial time investment for competitions, giving folks more time to work on "the other 90%."

Agents are much better at recovering from errors than they were. Only months ago, we'd see agents write code that didn't work, and then loop on trying to fix that until they ran out of time (or we ran out of money). Now, agents get to a working submission basically every time. For example, when building a submission for the Goodnight Moon competition, Codex received the error:

RuntimeError: The size of tensor a (125) must match the size of tensor b (40320) at non-singleton dimension 1

For folks who have been down in the guts of PyTorch, this will be instantly recognizable as "the way you are spending the next 4 hours." To solve it, the agent needed to know how Wav2Vec downsamples audio when building embeddings, which it simply remembered when it saw this error. Most practitioners would not simply remember this, and neither would agents from six months ago.

Agents are fast. Data science competitions are often framed as a search problem: if you wrote every possible computer program, you'd just need to hunt through your big pile of programs to find the one that wins.4 You can't write every possible program, but you can write a lot more programs with an agent than you can without. On that same Goodnight Moon competition, Codex generated 62 different submissions and still had hours left to spare.

Performance can be really good, and this is the worst these agents are ever going to be. Even with today's tools, our results are kind of the worst they could be. Consider the constraints we put on these experiments again:

- Run in 24 hours or less

- No human steering

- An unoptimized prompt with no additional scaffolding

- A single, mid-level consumer GPU

Each of these could be relaxed with a little bit of work. Coaxing Codex to run for 9 days on the Goodnight Moon competition instead of 24 hours resulted in its rank rising to #7 from #12 and its "progress to first" rising from 52% to 66%.

When asked to do better on a competition, agents generally do run longer and then output a better submission. They hit diminishing returns and top out prior to the top of the leaderboard, but still with very respectable scores.

Finally, actually running these agents has become so much easier. Near the beginning of these experiments we were running things like the OpenHands agent, which was great, but did require a good deal of setup and hand-holding. With the advent of agent harnesses coming from the frontier labs themselves, many of the rough edges have been made moderately smoother (though there are still a lot of rough edges as things are moving fast).

Current challenges¶

Simply getting the models to try hard enough for long enough is one of the biggest challenges both in the past and today. We found that we had to give the agents specific metric scores to beat otherwise they would train maybe a couple iterations and then stop. That can be seen in the example prompt: "I know a {metric} of less than {score} is possible. Do NOT give up until this is achieved. Do everything you can to achieve this in under 24 hours." These numbers need not be realistic—impossible scores serve just as well as realistic scores.

The agents seem very resistant to kick off long training runs. We'll often see competitors whose models need to train for multiple days to reach the top of the leaderboard. But these agents, even with scaffolding timeouts removed, will often not kick off training runs that will last more than 15 minutes. On the one hand, you can iterate a lot if none of your training runs last longer than 15 minutes, but on the other hand, you're never going to eke out that last bit of performance if all of your hyperparameters are tuned to complete training runs in relatively short periods of time.

Agents are actually overfitting more now than they have in our prior iterations of these experiments. As touched on in the Results section above, we found that very often, earlier versions of an agent's code performed significantly better than their final submissions. In Claude's attempt at the Conser-vision competition, it created validation splits and intended to perform five-way cross-validation. However, we found that it never actually executed the cross-validation and instead used a single split. We suspect this shortcut stems from the same hesitance to initiate long training runs. Better prompting strategies would likely alleviate this to a degree.

Hardware is still a significant constraint, which is not a limitation of the agents themselves, but still a limit on the overall workflow. We find that when running many of these sessions, most of the wall clock time is still spent in training compute (even despite short training runs). Significantly less time is actually spent with the model thinking or writing code. That is just a reality of data science competitions today. It seems like it'll be a reality tomorrow, too.

Non-determinism still plays a fairly large part in the final scores, though this has decreased a lot since we first started our experiments. A single session could get you a top 2% submission or a top 50% submission. Even Anthropic has referred to Claude Code as a "slot machine." An obvious solution to this is to try multiple times, but that runs into the next challenge that we saw.

Usage limits are real, especially for Claude Code. It's difficult to keep a session running for 24 hours without hitting usage limits or spending a significant amount of money. Obviously, this is great from the model provider's perspective, but it is a real constraint. Since we started running these experiments, this token consumption has gotten worse and then gotten better. Right now, the trend lines look favorable.

Sensitive data can't be tossed at random APIs. To get frontier performance right now, one needs to be using frontier models. Frontier models are not open-weight models, so they can't be run on your local hardware. That means to run an agent, you need to be shipping off some amount of competition data (or data derived from it) to another organization, e.g. OpenAI or Anthropic (or one of their partner providers). If the competition data is sensitive in some way, sharing the data isn't a good idea and competition rules often forbid it. Running agents locally is an alternative, but performance is roughly a year behind the frontier, which our experimentation suggests is pretty far, performance-wise.

It's easy to get out over your skis. We've seen this trend elsewhere, but in these experiments we assumed no expertise in data science on the part of the user. In reality, if you have little expertise in data science, it's very easy to quickly get to a 90% solution and then get completely stuck because you have no idea what's been built. That can also be the case here. Even as data scientists, we often don't have expertise in every data modality, every technique, every modeling strategy. If an agent builds you something that is far out of your wheelhouse, you have few levers to pull to meaningfully improve it.

Performance, it turns out, is not purely a function of raw intelligence of the base model. A lot of capabilities are elicited by the sophistication of the agents' scaffolding. For example, the latest Gemini models perform very well on a number of benchmarks and they find some use in our own work. But we found that the Gemini CLI is significantly less developed than the others we show here. Sessions would often end in either failure or scores significantly worse than the ones we see here.5

Opportunities and open questions¶

These small-scale experiments have helped us gain some perspective on big questions.

Are competitions still helpful?¶

Competitions serve various purposes beyond identifying the best model, but let's take that as the default case. From the perspective of a competition organizer seeking state-of-the-art models, little has changed. Previously, if you needed state-of-the-art, only the few top solutions mattered. Now with coding agents, if competitors only submit what their agents give them, there's little chance they'll perform better than the top-performing humans (who can also use agents). The top models in the past were created by humans with impeccable expertise and insight. The top models in the present are still created by humans with impeccable expertise and insight, they just now have more tools in their toolbox.

Do agents change who can participate?¶

We have some very technical "non-technical" folks on our team. They're terrific at reasoning about datasets, looking for potential pitfalls, finding new angles to look at a problem, etc., but knowing which versions of Python maintain ordered dictionary keys is not within their core competencies (can't blame 'em). Could they now coach an agent into developing a state-of-the-art model without needing to write code themselves (i.e. "vibe code to the top")?

Such democratization seems more likely if competitions approach the "aleatoric limit"—where data randomness fundamentally caps predictive performance. At this limit, traditional and agent-assisted approaches might converge on similar solutions or at least converge at similar levels of performance. We see that in the Flu Shot Learning results above: all the top scores are clustered closely together.

We've observed that top competitors often win multiple competitions without reusing code or architectures, suggesting some set of transferable skills. It's unclear whether these skills skew toward the highly technical or toward reasoning skills that allow for consistently finding profound insights in new datasets and domains, but we'll happily welcome changes that make for a bigger tent.

It does seem true that the skills to push modeling forward are different in an age of agents. Data science expertise is still important, but so is prompting, setting up scaffolding and tooling for the agents, and maybe even the skill of managing dozens of agents at once.

How big is the capability overhang?¶

OpenAI has defined the capability overhang as "the gap between what AI tools can do and how typical users are using them." In some real sense and in ways we've gestured at above, the models as they exist today are capable of performing better than we're eliciting here. Those capabilities are locked away for lack of better agent scaffolding and prompting. For example, we could relax our experiment rules a bit and instruct the models how to avoid overfitting. Human experts in our competitions are smart about avoiding overfitting, exploiting every small edge for hill climbing the optimization landscape, and knowing when to invest in long, compute-intensive training runs. Can we design better agent loops that truly have this kind of knowledge? How hard is that? How true is it that unlocking those hidden capabilities will translate into performance gains that matter? Questions and opportunities abound here.6

How are competitions going to evolve?¶

As we've mentioned above, agent performance can be improved by spending time locating weaknesses, trying different approaches, running experiments, etc. This sounds familiar. Instead of writing code that optimizes models, we're now writing code that writes code that optimizes models. This isn't AutoML; it transforms the data scientist's job rather than eliminating it. The required skills evolve, but human guidance, creativity, and oversight remain essential if the goal is to push forward the state-of-the-art.

Is 80% good enough?¶

In what contexts is the agent's "80% solution" good enough? Not every problem requires state-of-the-art performance to deliver business value. Often, a good-enough solution delivered quickly provides more organizational value than a perfect solution delivered late. If an 80% solution can be delivered in one minute (as opposed to a 100% solution in months), what does that imply about how work will change going forward?

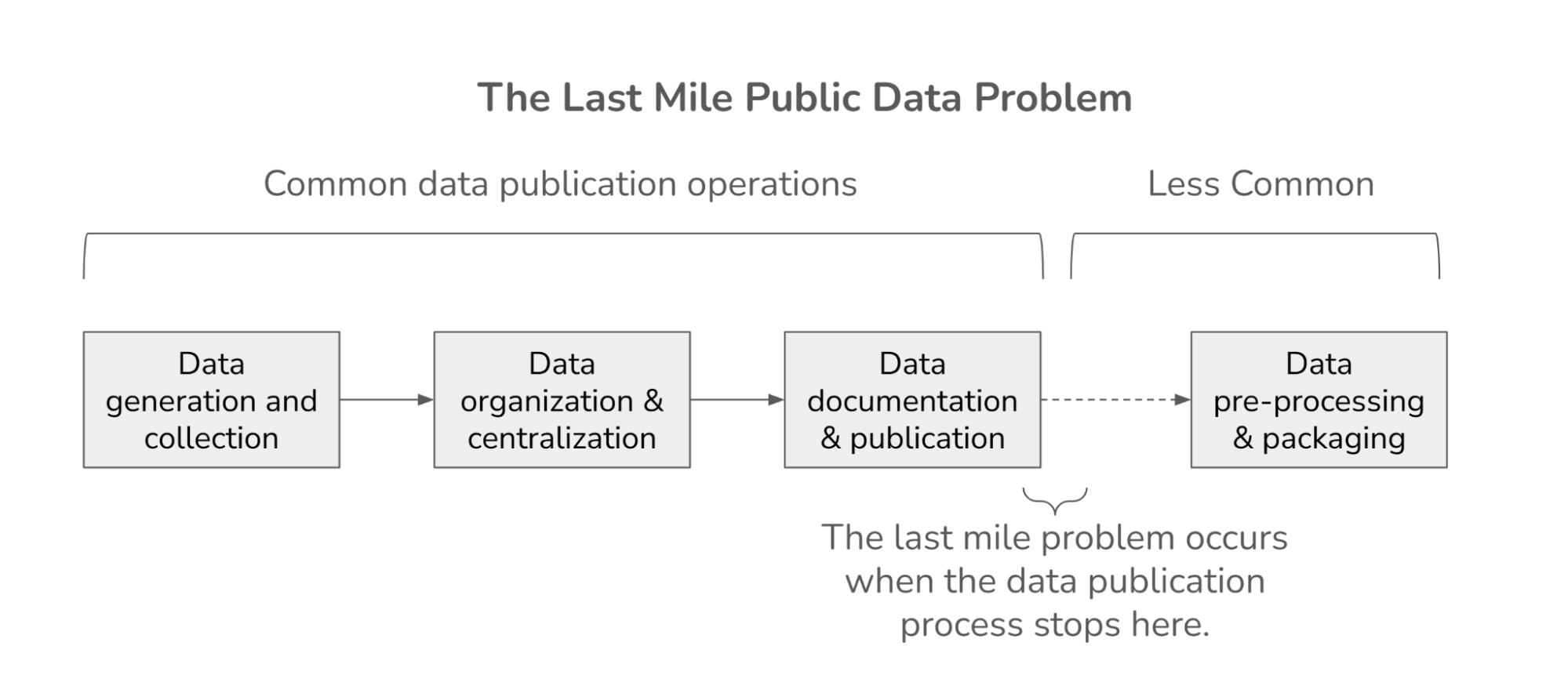

How do we account for taste?¶

These solutions are never really delivered in one minute. We could only assess agent performance for this experiment because DrivenData and our partners have done significant groundwork: selecting appropriate problems, gathering data, choosing metrics, writing documentation, and creating solution scaffolding. A single agent can solve many different data science problems, but the bulk of the work right now is curating and assembling the many problems rather than assembling the agent. We can recognize, curate, and guide in ways that remain valuable, and as the technical details see more and more automation, those skills will only increase in value.

Conclusion¶

Agents now reach a working, competitive submission in hours instead of days. They recover from errors gracefully and iterate faster than any human could. But they resist long training runs, overfit more than they should, and plateau before the top of the leaderboard. The 80% solution is essentially solved. The last 20% is not.

Once, humans were the best at chess. Then it was humans plus computers. Then, computers alone. The game of Go followed the same arc, just later because the search space was bigger.

Data science has a bigger search space still. Right now we're somewhere in the middle: agents reach 80% fast, but the best solutions still come from humans who can find their way to a winning submission but can't fully explain every turn along the path to that solution. Competitions have always been a way of surfacing that inexplicable knowledge, but now they're also a way of measuring how much of it is left. Humans at the top are currently doing something that agents can't. Can that something survive being named?

Banner image: image by Metropolitan Transportation Authority, CC BY 2.0

-

There are a lot of data-science-specific agents or AutoML libraries out there: Weco AI, AutoKaggle, DS-Agent, FLAML, H2O AutoML, AutoGluon, PyCaret ↩

-

We have also been testing Google's Gemini CLI with Gemini 3 Pro, but its performance has been significantly lower than the others and so isn't included. ↩

-

Most interactions with the agents consisted of just saying "Continue". ↩

-

Is that program called "Claude Opus 6"? ↩

-

With that said it's still very early days and Google has many irons in many fires, including Antigravity and Jules. ↩

-

Shout out again to all those doing the work to explore this space: Weco AI, AutoKaggle, DS-Agent, FLAML, H2O AutoML, AutoGluon, PyCaret, etc. etc. ↩