Almost all projects we work on at DrivenData share a fundamental need: getting data from a raw form into a final, processed form. Sometimes, a project's core goal is to create a data pipeline that will run in perpetuity and continuously process live feeds of data. More often, our data pipelines are enabling processes that serve a larger purpose, such as preparing data for use in training a machine learning model.

While most pipelines start out seeming like a simple set of sequential steps, the reality is that pipeline code often becomes a deep source of technical debt. Over time, complexity accumulates as capabilities are added. For example, we may need a development version that runs on less data. We may need separate production and dev environments. We need audit trails and observability to make sure everything processed correctly. We need error capturing and recovery, and we need the right decisions about when to stop and when to keep processing. We need the code to use resources efficiently through mechanisms like parallelization and caching. We need to be smart about incrementally updating versus re-doing every task from scratch. We need to augment a pipeline step with a different dataset that has separate re-process conditions. Soon, the code is a complex tangle that is hard to reason about and maintain.

In this blog post, I’ll discuss some of the challenges of creating data pipelines for data science projects. We hope to bring clarity to what makes pipelining complex, simplify implementation decisions, and help data science teams make beautiful data pipelines from the start.

Why is something seemingly simple so hard?¶

Imagine you need to prepare news article data to train a machine learning model to classify whether an article discusses data, AI, or machine learning. That doesn’t sound too hard! A simple Python implementation could look like this:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

def main(raw_data_directory: str = "path/to/raw_data"):

# Step 1: Load Data From a Folder

data = load_data(raw_data_directory)

# Step 2: Preprocess Data

data = preprocess_dataframe(data)

# Step 3: Train/Test Split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

data["article_text"],

data["label"],

test_size=0.2,

random_state=42

)

# Step 4: Define Vectorizer and Classifier

text_clf = Pipeline([

("vectorizer", TfidfVectorizer()),

("classifier", LogisticRegression())

])

# Step 5: Train Model

text_clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Step 6: Evaluate Model

evaluate_model(text_clf, X_test, y_test)

However, the load_data and preprocess_dataframe functions turn out to never be quite as simple as they seem. In the next sections, we will walk through a few common pain points that show up as you move from the drawing board to a fleshed-out pipeline.

1. The cold start problem¶

A new pipeline starts as a blank slate, and figuring out where to begin isn’t always obvious. There are countless ways to organize files and structure steps. Figuring out the right order of operations can take some work.

In our data-topic detection example, you might wonder: Should we store an intermediary data file with article text and metadata when we preprocess it? What metadata should we even track? When should we deduplicate the article data? What are the upstream dependencies of our processing steps?

Each of these decisions starts to introduce complexity into what was a simple pipeline.

Suggestions

- To start, sketch out the pipeline process visually to clarify dependencies and to ground alignment conversations about the pipeline in something concrete.

- As you structure the pipeline, separate transformation logic from pipeline orchestration (the code that runs each step). In our data-topic detection model starter code, we were on the right track with a

mainfunction as the entry point to the pipeline that calls external helper functions (load_data(),preprocess_dataframe(), andevaluate_model()) in sequential steps. - Structure pipeline steps as a directed acyclic graph ("DAG") so that each step depends only on its inputs and produces outputs for downstream steps, and each step flows forward to the next without ever looping back on itself. Relatedly, raw data must be treated as immutable (that is, don't overwrite the original data files; instead, save the results of the pipeline as new output files).

- Follow the software engineering principle of separation of concerns by breaking down complex logic and processing into modular functions that complete distinct objectives. Separation of concerns is a fundamental part of developing organized and clear pipelines. Modularity also makes each of the processing steps independently testable so you can have a test suite that ensures each granular step is doing what you expect. In our data-topic detection pipeline, we should isolate each task in our data preprocessing step and make separate functions that complete single objectives or operations:

def remove_duplicates(df: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame:

# TODO: implement deduplication

return df

def drop_missing_labels(df: pd.DataFrame, label_col: str = "label") -> pd.DataFrame:

# TODO: drop rows where label_col is null

return df

def normalize_text(df: pd.DataFrame, text_col: str = "article_text") -> pd.DataFrame:

# TODO: normalization steps

return df

def encode_labels(df: pd.DataFrame, label_col: str = "label") -> pd.DataFrame:

# TODO: map label values to numeric codes

return df

- Design the pipeline to be fully re-runnable end-to-end with minimal involvement. For example, make

main()runnable from the command line by adding an entry point so that the pipeline runs when you executepython identify_data_topics.py. - When we start to need more options and arguments at the command line, we like

Cycloptsfor building command-line interfaces. - It may be helpful to use DrivenData's Cookiecutter Data Science package when creating a new repository to house your pipeline. Using a well-defined, standard project structure will benefit you and your team in the long run.

2. Adding basic pipeline features is a worthwhile investment¶

Stringing the steps together isn’t enough. As soon as you start running the pipeline, you'll realize you have no idea what is happening while you are running it. Add-ons such as logging, metadata tracking, and error handling will reduce debugging time, yield results you can be more confident in, and help identify bottlenecks in the process. These add-ons are generally worth it and justify budgeting the up-front implementation time.

In the data-topic detection pipeline, logs could show exactly where a run failed and how long each step took. Adding tools to preprocess news articles in parallel can substantially reduce processing time.

Suggestions

- Add lightweight logging to capture per-task progress and errors, making debugging easier. We like

Loguru, an intuitive Python logging library. - Speed up long processes by parallelizing tasks (running independent work concurrently) where possible. We often use

tqdm, specifically theprocess_mapandthread_mapconcurrent versions. - Despite best efforts, pipeline runs often unexpectedly fail because of data errors or edge cases. Disk caching computationally expensive steps can be a huge time saver in these cases because it enables you to resume progress where you left off just before the error arose in a task rather than restarting all computations. The

@memoizedecorator works well for caching the results of functions. - Track and maintain metadata such as file hashes (which are fixed-length identifiers generated from a file's content using hash functions), unique IDs, and pipeline version for reproducibility. In our data-topic detection example, you could generate and track hashes of the article text with a function to confirm data isn’t being corrupted run-to-run. (Notice we also have logging and parallelization at the task level in this example!):

import hashlib

import pandas as pd

from loguru import logger

from tqdm.contrib.concurrent import process_map

def hash_text(text: str) -> str:

return hashlib.md5(text.encode("utf-8")).hexdigest()

def hash_article_texts(df: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame:

"""Add a 'text_hash' column to the DataFrame containing MD5 hashes of the 'article_text' column."""

logger.info(f"Hashing {len(df)} articles")

df["text_hash"] = process_map(hash_text, df["article_text"].tolist())

logger.success("Finished generating text hashes")

return df

- If the pipeline writes files, add an

overwriteparameter that raises an error (or skips writing the file) if a file already exists andoverwriteis set toFalse. This prevents accidentally overwriting existing files on subsequent pipeline runs. - Consider adding a

debugmode parameter to your pipeline that, when activated, runs the pipeline on a small sample of data so you can test changes quickly and make sure the whole pipeline runs as expected.

3. Varied inputs lead to complicated code¶

Inevitably, project inputs expand beyond a single clean data source. Each CSV file, scraped HTML document, JSON object, and API call comes with its own quirks and processing needs. Real-world data is messy: missing labels, odd encodings, and inconsistent formats often only reveal themselves once the pipeline runs at scale. And it’s not just data; every parameter or configuration you add can shift assumptions and introduce new branches in the logic.

In our data-topic detection pipeline, expanding beyond a single CSV with news articles could mean that you need to add separate cleaning steps for other formats. You might also discover that some articles in the training data are missing a label indicating whether the article discusses data, AI, or machine learning, or are in another language, or have source text from multiple articles stuck together. You have to account for these edge cases in the pipeline.

Suggestions

- Standardize and clean data early so later steps can assume consistent input. Preferably with a consistent, validated schema so malformed data fails early.

- Factor out shared utility functions instead of duplicating code for each source.

- Validate key assumptions early in the pipeline to catch anomalies, and fail loudly (e.g., raise errors) when those assumptions are not met. Raising errors early in the pipeline prevents wasted processing time for runs that fail. In our data-topic detection pipeline, if we need to ingest news articles from a website, our first step might be checking if the base URL for the website returns a "200" status code, indicating the website is active. If it doesn't return "200", we should skip processing because the site is down rather than issuing thousands of requests for articles that don't exist:

import requests

def ingest_articles(base_url: str) -> dict:

"""Ingest news articles from a website"""

resp = requests.get(base_url)

if not resp.status_code == 200:

raise ValueError(f"Base URL {base_url} returned status code {resp.status_code}")

# TODO: implement article ingestion

return articles

4. Tech debt in a world of changing requirements¶

Project goals, requirements, and data formats change over time. This can create headaches when the existing pipeline needs to be refactored to account for processing conditions that didn’t initially exist. How will you handle backwards compatibility? Do you deprecate the "old way" of doing things entirely, or make the "old way" one of many processing options that can be triggered by calling certain parameters?

To avoid tech debt, it’s tempting to design a pipeline that is scoped out to be compatible with many processing scenarios from the start. But this, too, comes with downsides, as code will often be unnecessarily complex to preserve flexibility that you might not actually need.

In our example, maybe you first designed the pipeline to process a single labeled dataset. Later, you get access to additional datasets and decide you need to track metadata fields such as article author and publication date by source. Meeting these new needs means adjusting the data organization, adding new processing steps, and sometimes rethinking the overall pipeline structure.

Suggestions

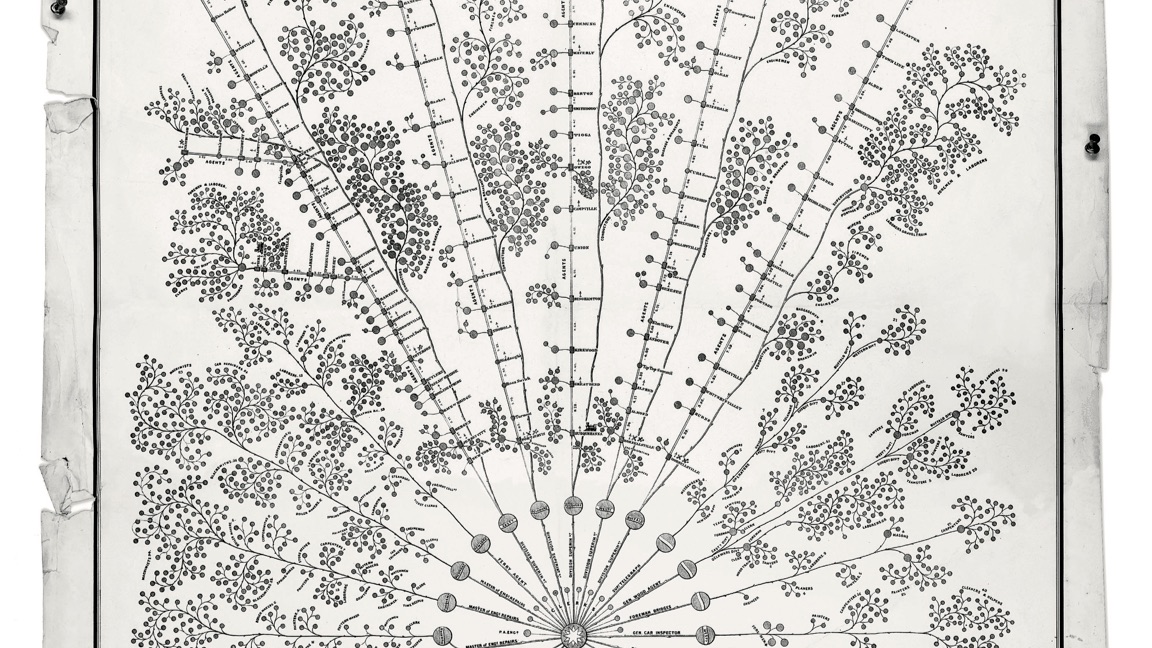

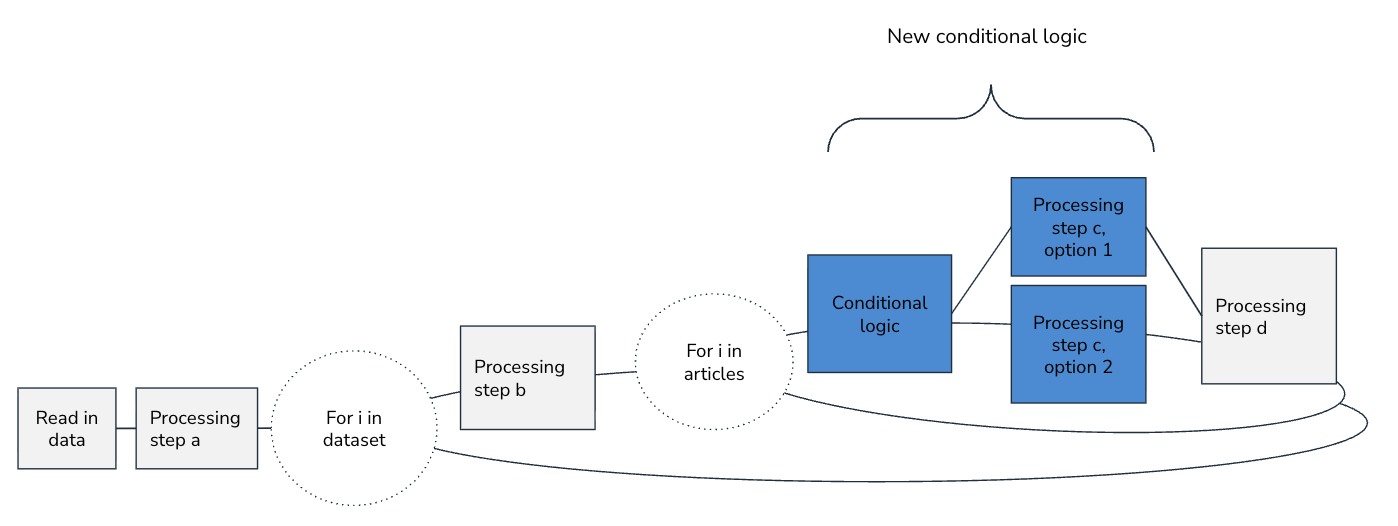

- Changing goals, requirements, and data sources is sometimes unavoidable. Before diving into the refactor, visually map out options for updated pipelines, consider the level of effort and tradeoffs required for each option, and align with teammates on a course of action. We often make pipeline visualizations on simple annotated slides:

- Sprawling if/else logic across the pipelines for different data sources is a code smell. Your goal should be to standardize what you need to at the moment the data source is first initialized and then share as much unchanged pipeline code as possible.

- Tech debt comes into play for what packages and libraries you choose as well. When multiple library options are available, try to pick the most well-maintained and widely used libraries up front. Look at how long it's been since the most recent commit to the package's source code repository, and how many stars the repository has on GitHub. Well-maintained and widely used packages are less likely to introduce new bugs down the line as new versions of other dependencies are released.

- Be deliberate about where flexibility is truly valuable. Communicate with your team about the tradeoffs, and make simplifying assumptions where you can.

5. Beauty takes time¶

There’s always a balance to strike between getting something working quickly and building something clean and easily maintainable. Extra beautification efforts, such as clear file names, informative comments, and tidy dataset creation, pay off in the long run. You or a teammate will inevitably return to make modifications to the pipeline, and clear, well-documented code will make it easier to understand and less prone to having bugs accidentally introduced when updating it. But, if there is a quick deadline, it may be reasonable to take some shortcuts.

In our data-topic detection example, naming an intermediate dataset processed_labeled_articles instead of test_dataset_3 makes the pipeline clearer without slowing you down. Refactoring article processing code that works, but is duplicative or inefficient, requires more effort; whether the refactor is worth it is a judgment call.

Suggestions

- The level of investment in the pipeline development should be proportional to how long one run takes and how often it will be run end-to-end. If the completed pipeline will be run just once, it may be enough to make a pipeline that produces accurate results relatively fast. In cases where the pipeline will be run often, it is usually worth it to make the pipeline accurate, efficient, and refactored for clarity and maintainability. It is a good idea to align with your team on how much polish is needed before diving into any big code refactors.

- Pick descriptive names for files, functions, and outputs from the start.

- Include descriptive docstrings in functions. We've found that LLM coding assistants (e.g., Copilot) or tools that set up docstring structures (e.g.,

autoDocstringextension for VS Code) make properly documenting functions quick and easy. - Adding type hints (explicit input/output types in function signatures) is helpful for clarity and aids in error detection, especially when used alongside type-checking tools like

MyPy,ty, andPyright. - Refactor small inconsistencies as you go instead of letting them pile up. Likewise, format code as you go using automatic formatting tools, like

BlackorRuff. - Pipelines are often parameterized: the code can be configured to run in different ways by changing inputs (parameters) rather than modifying the code itself. For each run of your pipeline, you should record the configuration used, environment variables, timestamps, and pointers to log files or outputs for future reference. You can, of course, do this recording manually (e.g., copying the exact command you ran, including parameters, and other pertinent information into a tracking file or notebook). But we recommend capturing and persisting this information automatically using config files/ environment variables for setting pipeline parameters and automated run tracking systems for recording run metadata.

Embracing challenging pipelines with intentional effort¶

Making data pipelines is an aspect of most data science projects. And it often seems so simple from the outside: just move data from A to B. As soon as you start building, though, the hidden complexity emerges.

There are many tools you can use to facilitate pipelines rather than creating Python pipelines from scratch (e.g., Dagster). But these tools add learning curves and complexity. It often makes sense to start an implementation from a Python script and then invest in more tooling later if needed.

With some of the best practices we discuss, we can prevent some of the pain points and common pitfalls that domain-specific tools try to solve for and make it easy to have reliable, trustworthy pipelines with minimal dependencies and the right level of investment.

For further reading about general data science best practices, DrivenData's ebook The 10 Rules of Reliable Data Science is publicly available for download.