This commentary is related to the shakeup in leadership at Open AI in November 2023. Here’s a good timeline of coverage of the happenings. I hope the points made here stay relevant even as the situation evolves.

OpenAI's Structure¶

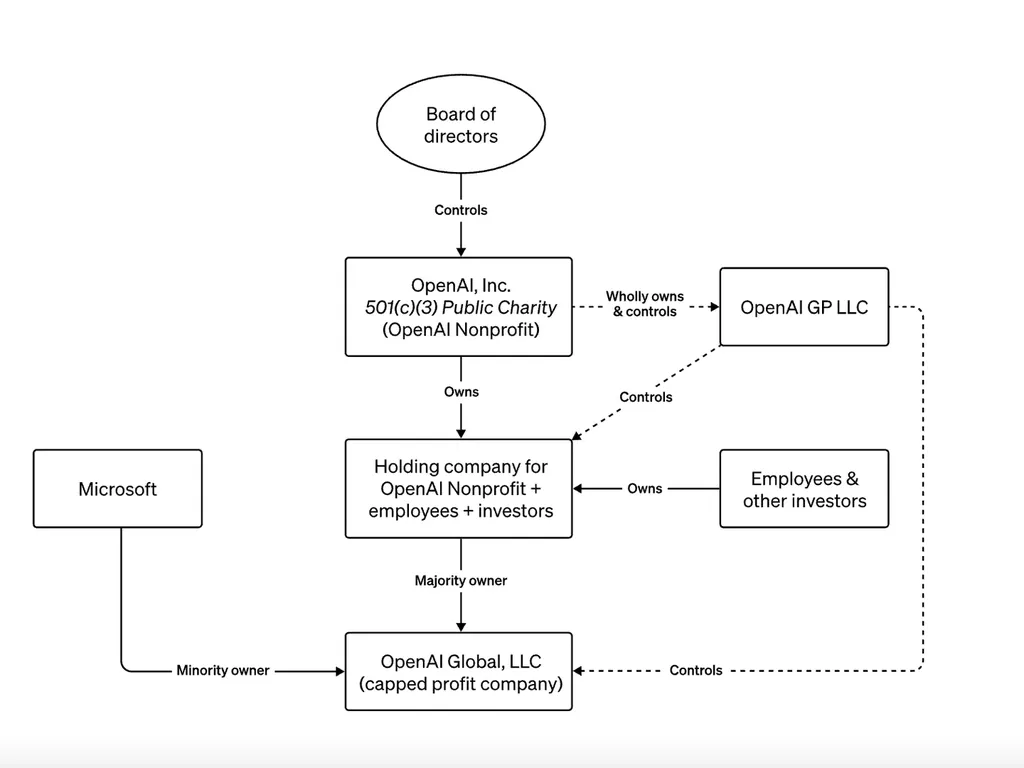

I remember when OpenAI launched I had an interesting conversation with my wife. She’s a tax attorney, and when I described their novel new structure with a brand new kind of legal entity, she rolled her eyes. Of course, as she explained, there was no new kind of entity here—new entity types are the domain of legislators not entrepreneurs. Instead they had frankensteined together a few entities in a way that was unusual, but not unprecedented.

And, perhaps unsurprisingly, Frankenstein’s monster has ransacked the village.

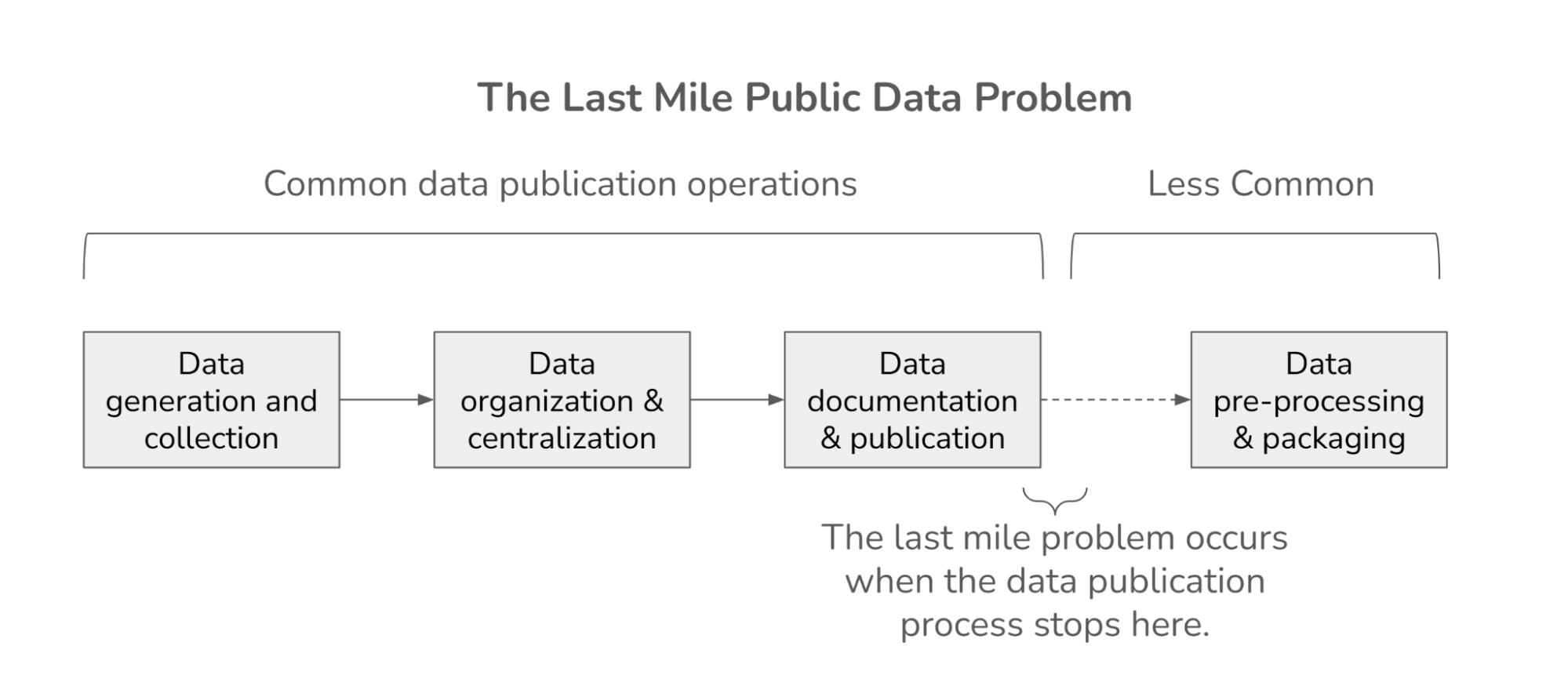

OpenAI entity structure (from OpenAI website)

The much emphasized takeaway of the entity structure is that a non-profit owns the for-profit OpenAI entity. Seems great. OpenAI is a nonprofit. Now let’s talk a little bit about what this means in practice.

Nonprofits and tax-exempt status¶

When I started DrivenData, we asked a lot of people, including the aforementioned spouse, for advice on being a nonprofit versus a for profit. In the US, being a non-profit means that your corporate entity (which is like any other corporate entity) is exempt from federal income taxes under the Internal Revenue Code, for example, under section 501(c)(3). As I learned at the time, the federal government doesn’t have anything to say about profit at all. The Code doesn’t refer to “nonprofits” and instead specifies tax exempt entities which qualify such as “charitable organizations.” The deal is that in order to qualify, the organization must serve a charitable purpose (if you’re curious, you can read for yourself what that means) and not have any benefit inure to a private interest—i.e., shareholders or individuals. Assuming all requirements are met, the organization is generally exempt from federal income tax and can accept tax-deductible contributions from individuals and entities.

The last point about accepting tax-deductible contributions is more important than I thought it was. Every social sector organization gets asked by their funders about their “sustainability plan.” A sustainability plan is a plan for how the organization will continue to bring in enough funding to keep operations running. If the answer is grants and individual donations, it’ll need to get the 501(c)3 exemption to accept these funds and provide the tax benefit to the donors. If the answer is that you’ll have a fee for your services, you may be better off not starting out by jumping through the hoops to qualify for the 501(c)3 exemption. In this case, if you don’t make much profit, you won’t pay much tax anyway. Plus, you reserve the optionality to file for 501(c)3 if it turns out your funding will instead be grants and donations. Not filing for a 501(c)3 exemption does not preclude you from having a mission and operating according to it—despite the omnipresent misconception that corporations have a legal obligation to maximize shareholder value.

Governance for AI organizations¶

So, with all that said, I had some background and interest in thinking about the organizational structures that facilitate organizations that want to use data, AI, and machine learning for social good. In fact, I was interested—and maybe a little hopeful—when I saw that OpenAI, as a leading AI lab, had made an interesting structural choice. I have always been bullish on the social sector spending more time building core technology and infrastructure.

And, especially when it comes to AI, there is at least a defensible position that AI development is so important that we want it not to be done by unfettered capitalist entities. We’ve all seen how negative externalities get neglected by corporate entities, and it’s reasonable to believe that many of the harms of AI will be externalized from the builders’ business models. Without the profit motive dominating decision making calculus, charitable organizations may be better positioned to design and build technology in a way that reduces these harms.

So, that’s where we get back to OpenAI. The absolute best case explanation of the board’s firing of Sam Altman is that they were concerned his actions were not in line with the charitable purpose. I have no special insight into if this is the right decision from a mission perspective. However, the lack of concrete evidence presented by the board indicates it was a rash decision driven by interpersonal conflict, and this interpersonal conflict has thrown OpenAI into turmoil. And, while I’m not personally worried about ChatGPT from an AI safety perspective, imagine if OpenAI had made advances towards superhuman intelligence and it was only at that point that the governance of the organization had been revealed to be so incredibly unstable. We got lucky that we have relatively quickly learned just how shaky a foundation a “mission” alone can be.

Interestingly, when these breakups happen at corporations, they’re usually managed better, or at least more predictably. There are three simple reasons for that. First, a shared financial interest aligns incentives to resolve political disputes amicably. Second, major investors put managers on boards that (at least in theory) provide experience managing crises within organizations. And third, the board would likely face a lawsuit if a CEO with the success metrics of OpenAI was fired without clear and explicit justifications. This isn’t an argument for unfettered capitalism. It is just an observation that financial incentives sometimes align in a way that provides stability for an organization, and stability itself can be a substantial public benefit.

What have we learned here?¶

I’ve got three takeaways from the saga. First, the structure itself of OpenAI does little to enforce publicly beneficial outcomes, and we should ensure both public pressure and strong regulatory regimes are part of our accountability mechanisms for AI organizations. Second, organizing as a tax exempt entity does not in itself make any guarantees of good governance, and may even—through its lack of personal incentives beyond influence—create a more challenging environment for effective governance. We should expect more disagreements within social sector organizations, not fewer. And finally, as with every type of organization, the sustainability model trumps all. In the end, Microsoft is OpenAI’s primary supporter right now, and so if OpenAI wants to stick around, they need to do it in a way that keeps Microsoft happy.

This makes now a good time for social sector organizations to look inside and ask themselves about mission, accountability, and how easily board decisions are driven by the politics of internal factions. What are our governance procedures? How do we go about having good-faith disputes about differences of opinion on what best serves the mission? How does this input go into a deliberative process that guides us to the best outcomes without letting organizations flail about wildly? How do we plan for stability and resilience of organizations operating important technologies in times of crisis?

These are not questions that can be outsourced to your corporate structure and a 500-word charter of mission.

As always, I'm interested in your comments and feedback! If you're interested in practical ethics training for AI practitioners, responsible AI strategy, or implementation with likeminded builders don't hesitate to reach out.